noise is disturbing my slumber. Half asleep, I realize it is my alarm. Hitting the off button, I try to wake up fully. Today is Sunday and today's agenda is a half-day tour of the Weinerwald (Viennese Wood) - there will be three stops on this short bus tour: Mayerling, Heiligekreutz, and a grotto. I will be leaving Austria tomorrow and I thought a short tour would be a nice way to spend my last day.

Getting dressed, I head out to the bus stop. Today, instead of the Opera House, I need to get to the main bus terminal – so, bus to the U-Bahn station then the subway to the main bus terminal. Except, this is not so easy to find. I am trying to follow the directions on my GPS but I am hopelessly turned around. Part of the problem is that this is also a major highway interchange so the road crossings are limited. I fear I will not make it to the bus before it leaves.

After 20 minutes of walking, I finally find the loading zone for my bus. Huzzah!

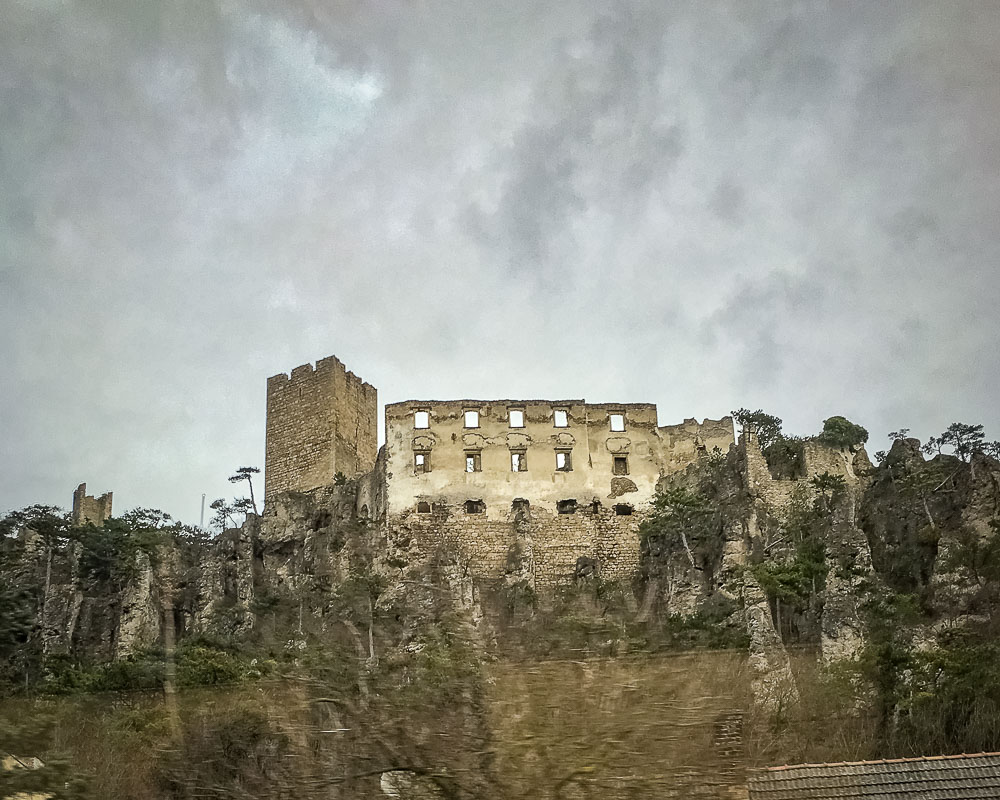

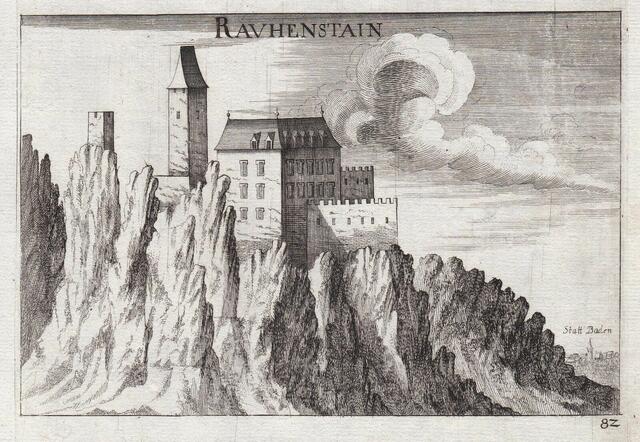

Sitting on the bus on the way to Mayerling, I look out the window at the passing countryside. Lots of fields and small villages but one structure catches my eye. High on top of a rocky hill is the large ruin of a castle (or fortress). This is the Burgruine Rauhenstein (the ruins of Castle Rauhenstein).

Even as a ruin, Rauhenstein still dominates the valley from afar. Situated on the northern slope of the Helenental on a 50-60 m steep, rocky slope overgrown with pines, it is one of the largest castles around Vienna. It had more than 20 rooms, could accommodate about 100 people, and had good sightlines to two other castles - Rauheneck and Scharfeneck. The vulnerable northwest side had been reinforced with a 9 m deep ditch and the walls of the 20-meter-high tower are three meters thick at the base.

It was probably built in the last third of the 12th century. Its location was strategic, as the road through the Helenental was the only practical connection through the Vienna Woods to the west. Rauhenstein is first mentioned in 1186 and in the 12th and 13th centuries, the castle was owned by the Babenberg ministerial dynasty of the Tursen. It is rumored that a suitor brought the daughter of Heinricus de Ruhensteine saffron seeds from a crusade and that all the saffron cultivations around Baden – until the 19th century – go back to these seeds. The Tursen line probably died out around 1299 and the castle passed through marriage into the possession of the Pillichsdorfer family around the middle of the 13th century and, from them, Hans III von Puchheim in 1386.

In 1466 Wilhelm II of Puchheim rebelled against the Emperor and, in the same year, the Empress’ entourage on its way from Baden to Heiligenkreuz is said to have been attacked by Wilhelm II of Puchheim servants. Although they were ultimately unsuccessful, the emperor ordered a punitive retaliation and Rauhenstein was besieged and eventually taken. The castle was partially destroyed during the siege and Wilhelm II of Puchheim was outlawed. Since that time, Rauhenstein was a possession of the emperor and was administered by keepers. During the Hungarian Wars, the castles of Rauhenstein, Rauheneck, and Rohr were destroyed. Of the three, only Rauhenstein was slowly rebuilt.

In 1529, Rauhenstein was destroyed by the Turks, which was repaired in 1531. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the castle was the center of a large district court, which also included the former lordships of Rohr and Rauheneck. The castle was sold several times – once in 1583, in 1602, and again in 1617. At that time, the castle became an administrative seat but by 1635 it was already abandoned and no longer maintained. In 1644, Rauhenstein was pawned to pay for debts. From then begins an increased turnover of the property – in 1658, 1665, and 1678. In 1683, the castle had already become a ruin due to the Turkish invasion, the frequent change of ownership, and the numerous insolvent owners. By 1705, not only were most of the roofs on Rauhenstein missing, but also windows and doors. It is often written that a “roof tax” had been the castle’s undoing – that, in order to save money on a tax on the area of roof a property had, the roofs of Rauhenstein were mostly removed that turned it into a ruin. This is untrue, however, for by that time Rauhenstein had long been uninhabitable.