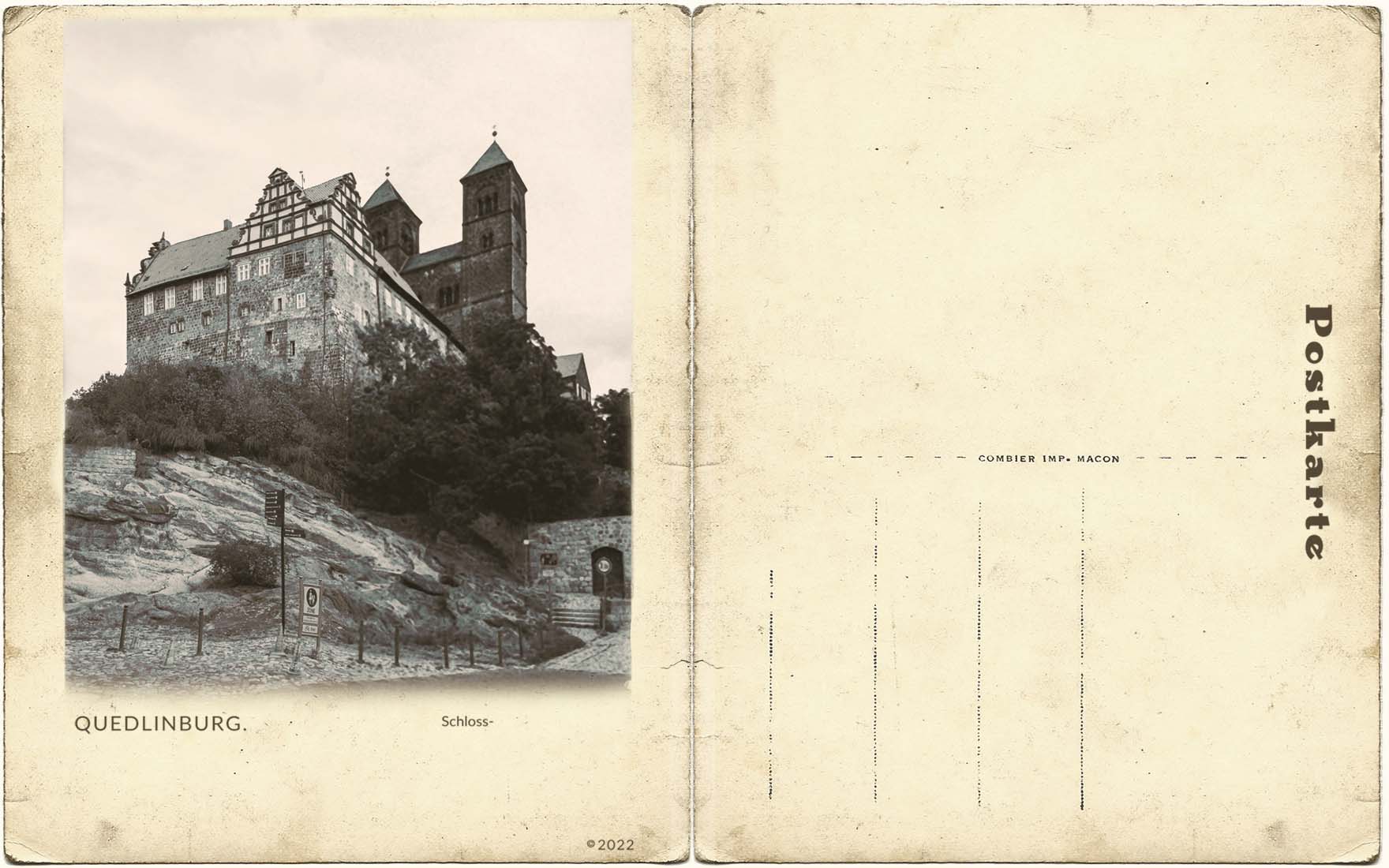

fter our tour of the Altstadt, the tour guide sets us free to explore on our own - with strict instructions to be back at the bus at 3:00. During the tour, I have noticed the fortress up on high, overlooking the city. This will be my first stop.

The steep cone-shaped rock had been seen as a strategically beneficial vantage point on the northern edge of the Alps for centuries. In 1077, the archbishop of the time ordered the erection of a castle above the city of his residence. The structure is Fortress Hohensalzburg and is considered to be one of the largest existing 11th century fortress complexes in Europe.

Indeed, although the fortifications were built to protect the prince bishops and the principality itself from attack, the fortress never faced a real siege and most of the time the prince bishops lived in the palace at the heart of Salzburg town. As such, the fortress is often seen as a symbol of the desire for recognition by the prince bishops.

The fortress was constructed in three main phases with the last phase starting around 1500.

I follow the others weaving my way through the small streets and alleys, slowly climbing upward towards the fortress on high.

At the top of the street – or the base of the giant rock upon which the fortress is built – there is a quick and easy way to get to the top…a funicular railway. The 180 meter long cable railway is said to be the oldest operating funicular railway in Europe.

In 1892 in response to the increasing importance of tourism, the funicular railway was modernized using a curious propulsion system. Water was pumped from the Alm canal that passed by the bottom station up to a reservoir at the top. From there, the water was diverted to the undercarriage of the railway car waiting at the top station, and its weight pulled the second wagon upwards from the bottom station on the same cable. That’s why the locals called it the “Tröpferlbahn“ (Droplet Railway).

Following a loose remembrance of the walking map of the fortress, my first stop is the Hasengraben Bastei (Hansengraben Bastion). The view of the Salzburg to the south is amazing.

The massive Hasengraben Bastion was built during the third major period of construction, 1618–1648, in which the castle was converted into a fortress. The Archbishop Paris von Lodron ordered the trench filled in to build a platform for large cannonry (due to their weight the towers could no longer support them). The defense line runs in a half circle and could hold against any attacker coming from the south.

Leaving the Bastion, I come across the Stallungen und Salzmagazin (Sable and Salt Magazine). Walking around, on one side of me is the wall’s wall and on the other side of me are the walls of huge formidable buildings. This fortress is really like a fortress within a fortress.

In the 16th century, stables were added to the outer ring wall, which is more than three meters thick at the base, on the inner side of the wall at ground level, and a salt magazine was built above it. The narrow and long building bears the coat of arms of Johann Jakob Kuen-Belasy on the courtyard side from the year 1566.

The building was used on the ground floor mainly to house living “provisions”, i.e. oxen, dairy cows, and sheep. Above them (also for preservation of meat) salt was stored. The stables and the salt magazine above were rebuilt during the time of the Thirty Years’ War.

The Granary stands out among the whitewashed buildings with its lovely burnt orange color trim and edging.

One of the oldest preserved buildings in the fortress, built in 1484. It stored enough grain to feed up to 300 people for a year. The grain was not stored in sacks though. Instead, the grain was poured onto the wooden floors, and that’s how it got the name “Schüttkasten” (pour warehouse). A wooden roof and floor allowed the grain to be ventilated, so that it could be stored over long periods without getting moldy. The cellar of this building once stored up to 115,000 liters of wine. Today, the masonry vaults support the four massive floors.

Continuing on, I come across the cistern. The cistern has an interesting story behind it – though I think that most everything has an interesting backstory.

Around 1500, during the greatest progress in the construction of the fortress, the cistern was built. The archbishop at the time – reportedly the last medieval ruler of Salzburg – had so angered the population of Salzburg with his authoritarian leadership that he needed distance from the “common folk.”

For this reason, he expanded the fortress and changed it from a defensive structure to a residence. But water would be a problem – especially since the fortress sits on a large rock. With a cistern, rainwater was collected so that the water supply was secure in the event of a siege. The cistern goes back to him.

However, the peasants’ revolt, for which had been so readily prepared, occurred with his successor – a three-month siege in which the reservoirs barely supplied enough water. New, larger cisterns were ordered to be built after that. Traces of this time can be found all over. The Archbishop’s coat of arms can be found 58 times on the walls of the fortress and consists of a turnip.