leave the Greek and Roman antiquities behind and enter the gilded life of the nobility. So much gold, so much ornateness, so much opulence in their everyday life.

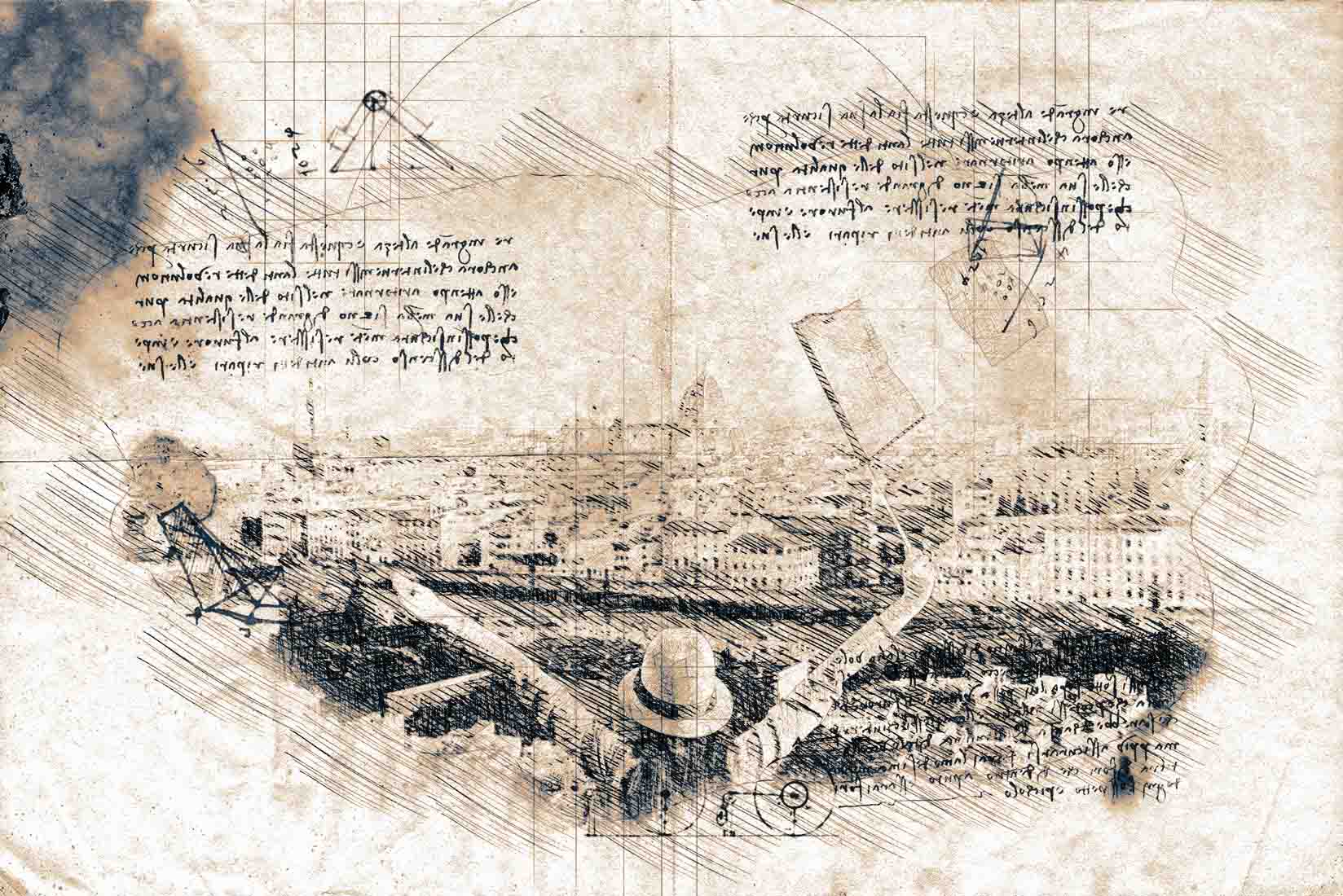

Indeed, the Kunstkammer Wien is a conglomeration of several individual collections assembled from various patrons. This gives this part of the museum an interesting hodge-podge feeling. A separate part of this collection are finely made automatons, clocks, calendars, and calculators – supposedly representing the latest technology of the time. Indeed, the Kunst- und Wunderkammern (arts and natural wonders) of the Renaissance and Baroque periods attempt to reflect the entire knowledge of the day.

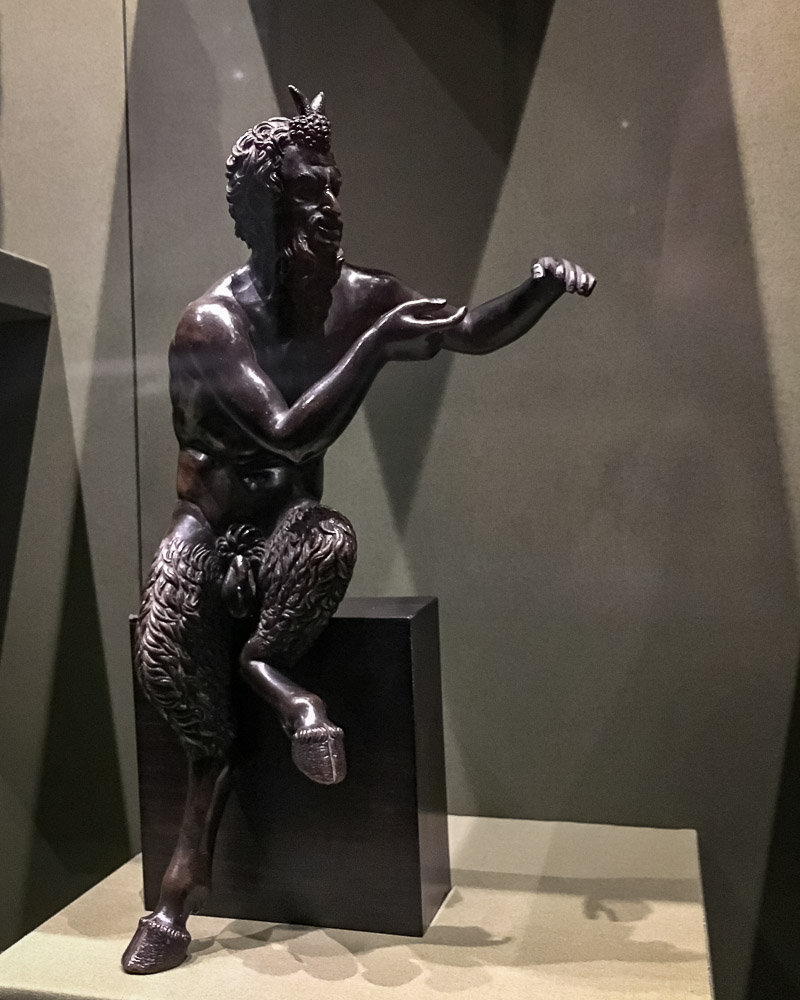

A collection of about 800 tapestries that were originally used to decorate the royal palaces was added in 1921. The Picture Gallery had its origins in the 16th and 17th centuries and by the end of the 18th century was in its present form. In the 17th century, works of semiprecious stones – which were still very popular at the Vienna Court – as well as objects of turned ivory, carvings of rhinoceros horn and miniature wax models were added. Many of the works of the goldsmith’s and lapidary’s art date from around 1660 as do the bronze statues.

Particularly desirable were rare, curious, and unusual objects. From the late Middle Ages to the Baroque, Habsburg emperors and archdukes collected exotic and uncommon materials such as shark’s teeth, which were considered to be dragon’s tongues (!).

The gluttonous brother-in-law of Maria Theresa, Duke Karl Alexander of Lorraine, owned wonderful tableware. Only four candelabras, two sauce-boats and the epergne reproduce here have been preserved from his large golden table service. On a base in the shape of a tray an open work basket is placed as a central piece, supported by four candelabras. Out of the basket sprout the most delicate porcelain flowers, which however, are not original. Below several small Chinese porcelain figures and around this centre group are arranged two pairs of porcelain oil and vinegar jugs set in gold, two golden sugar shakers and four little porcelain bowls with lids. These last items are dated 1794 and bear the mark of the Vienna Augarten manufacture. Jakob Frans Van der Donck (Brussels 1725-1801) was commissioned as early as 1770 with the extension and remodelling of this set. In carrying out his work he re-used older parts of the epergne. Except for the tablet dated and signed by Fonson to the left and right of the Duke’s coat of arms, we are not able to establish what other parts of the original work by Fonson are still preserved in this epergne.

Leaving the knickknacks behind, I enter the Picture Gallery. The Picture Gallery was developed from the art collections of the House of Habsburg. The foundations of the collection are 16th-century Venetian paintings, 17th-century Flemish paintings, Early Netherlandish paintings, and German Renaissance paintings. This part of the museum smells of centuries oil – like time itself trapped in the hues spread over the canvases.

One painting catches my eye – The Three Phases of Life and Death (1509). It is described: Above the head of the young woman lost in the contemplation of her image in the mirror, Death holds the threat of an hourglass that has run out. The elderly woman on the left can barely keep Death at bay. The latter is also reaching for the veil of Youth, behind which a boy is hiding on the other side. He sees the course of life and its inevitable end – at that moment – only vaguely.

I have been in the museum for several hours and I am very tired (and hungry). I have made it through most of the rooms but to be honest, I have not given the Picture Gallery all the attention it deserves. When I spend more time sitting than looking at the beautiful paintings – it is time to leave. I say a farewell to the Art History Museum and step out into the late afternoon drizzle.