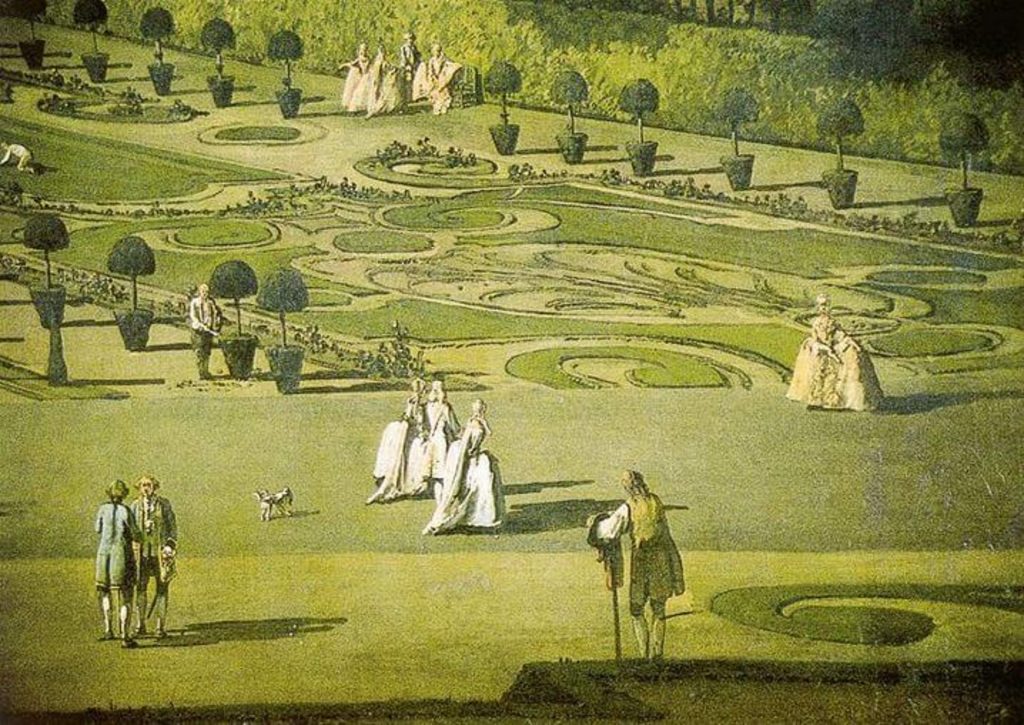

he garden is huge. Indeed, it is often called the park at Schönbrunn complete with a labyrinth and a zoo. A LabyrinthI I have always wanted to visit one! Oh, unfortunately the labyrinth is closed in the winter months. I continue my way through the expansive garden.

In 1569 the palace and land passed into imperial possession through Emperor Maximilian II. The Roman-German emperor was mainly interested in laying out a pleasure garden and game preserve in order to indulge his twin passions of collecting and hunting, the latter a passion which was shared by many other members of the Habsburg dynasty. Thus, the gardens were not only intended for the keeping of native game and fowl but also provided space for exotic birds such as peacocks and turkeys – a standard feature in princely gardens of the time. After the gardens were destroyed by Hungarian forces in 1605, the damage was provisionally repaired and the estate was subsequently only used for hunting.

Eleonora of Gonzaga had magnificent formal gardens laid out around the palace which became the setting for frequent court celebrations and festivities. Her niece and successor continued to extend the gardens. In the mid-seventeenth century numerous open-air performances took place in the ‘famose parco di Scheenbrunn’. This glittering lifestyle came to an abrupt end when Vienna was besieged by Ottoman forces in 1683 and the palace and park at Schönbrunn were destroyed. In 1686, Leopold I decided to give the estate to his son and successor, Joseph, and commissioned a magnificent new palace for the future emperor. Having at first produced a set of somewhat utopian designs, the architect eventually came up with a practicable design for a large hunting lodge. Work started on the hunting lodge in 1696 and four years later it was ready for occupation. However, the lodge was not fully completed before Joseph’s death in 1711 because of financial difficulties from the War of the Spanish Succession.

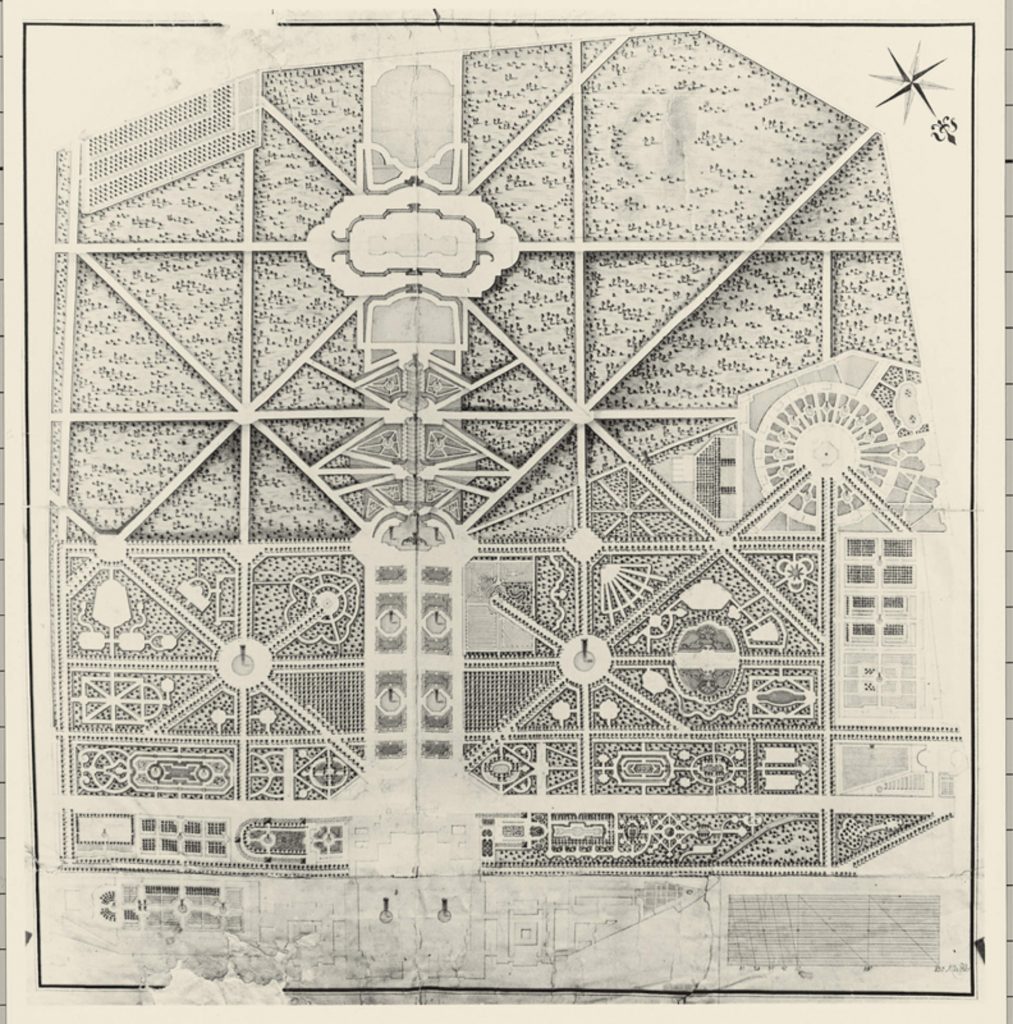

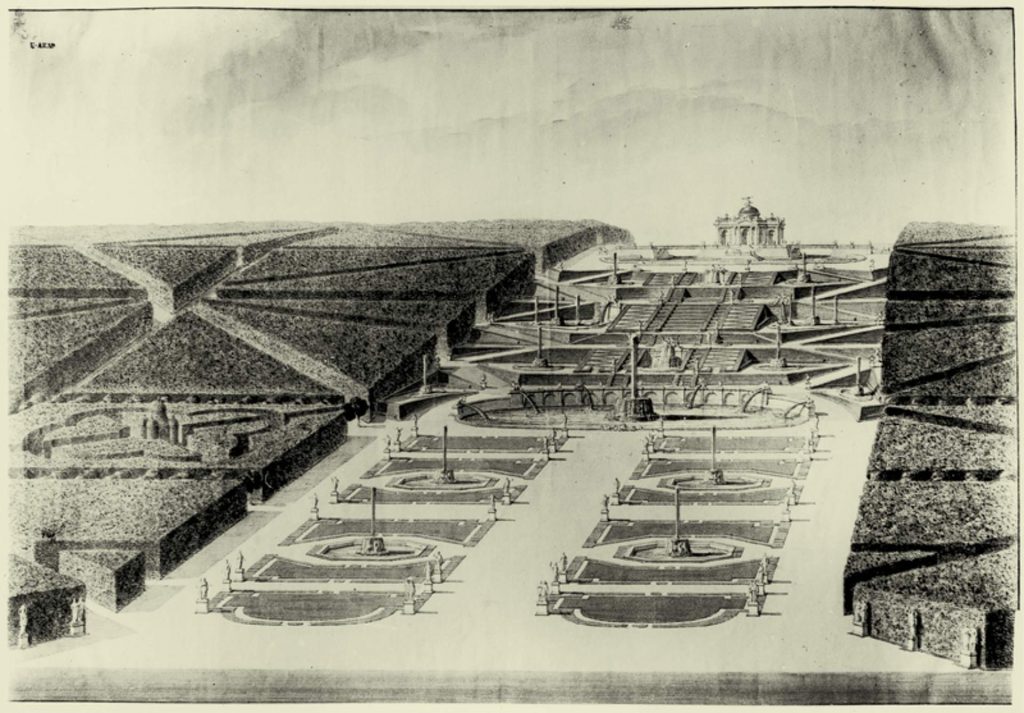

Plans for the gardens date from as early as 1695. Wide avenues articulated the early Baroque gardens, which probably also contained a maze – an almost obligatory feature for gardens of this type and age – as well as a circular orangery garden. In 1728, Emperor Charles VI took over the unfinished lodge but visited it only to shoot pheasant. He is said to have gifted it to his daughter Maria Theresa, who had allegedly always cherished an affection for the palace and its gardens. The park was extended and redesigned – Schönbrunn’s Baroque gardens were intended to be an impressive symbol of imperial power, and were seen as an external continuation of the magnificent interiors of the palace.

While the palace and gardens were virtually completed by 1760, Schönbrunn Hill, the slope rising behind the Great Parterre, was still merely an unadorned aisle cutting through the surrounding woods. Elaborate plans for this area were drawn up by the court architect but Maria Theresa regretfully decided in favor of a simplified solution, with the Neptune Fountain at the foot of the slope and the Gloriette crowning the top of the hill. The hill itself was to be accessed by simple paths zig-zagging up the slope, instead of the elaborate terracing foreseen in the original plan.

In order to accommodate the imperial family’s extensive botanical collections, the Dutch Botanical Garden with its hothouses was expanded with a further hothouse sited near the present-day Botanic Garden. The Dutch Botanical Garden was later cleared when the glass Great Palm House was erected in 1880-1882. The gardens surrounding it were also landscaped at the same time. Not far away, erected in 1904 as the last building to be commissioned by the imperial family, is the Sundial House, which was originally intended to house the so-called New Holland Collection. Today the house – renamed as the Desert House – contains various examples from the valuable collection of succulents.

My first stop is the top of the stairs at the back of the palace. I wait for the remaining people and Instagrammers to take their photos so I am unconstrained for time. This vantage point allows me to see the entire vista – and what a vista. Even with the grey…

The garden axis points towards a 60-metre-high (200 ft) hill, which, since 1775, has been crowned by the Gloriette structure. Maria Theresa decided the Gloriette should be designed to glorify Habsburg power and the Just War and thereby ordered the builders to recycle “otherwise useless stone” which was left from the near-demolition of a neaby palace. The Gloriette was destroyed in WWII but had already been restored by 1947.

The Neptune Fountain at the foot of the Gloriette hill was designed to be the crowning monument of the Great Parterre and work on the fountain began in 1776. The retaining wall merges into the slope of the Gloriette hill and includes a railing adorned with ornate vases.

Neptune stands atop the grotto at the center of a group of figures in a shell-shaped chariot holding a trident. A nymph is seated to his left. Appearing at the base of the grotto are four tritons— half-man and half-fish—who are part of the sea-god’s entourage. This image of Neptune commanding the watery dominion was a common symbol in 16th – 18th century art as a representation of monarchs controlling the fate of their people.

The sculptures in the Schönbrunn Garden were created between 1773 and 1780. The Great Parterre is lined on both sides with 32 over life-size sculptures that represent mythological deities and virtues. Other sculptures are distributed throughout the garden and palace forecourt, including fountains and pools.

| Amphion was the son of Zeus and Antiope. Amphion became a great singer and musician after Hermes taught him to play and gave him a golden lyre. He and his brother built the walls around the Cadmea, the citadel of Thebes. Amphion’s musical skill was so great that when played his lyre, the stones simply moved into place. |

Mars and Minerva. In ancient Roman religion and myth, Mars was the god of war and an agricultural guardian, a combination characteristic of early Rome. He was the most prominent of the military gods in the religion of the Roman army. Minerva is the Roman goddess of wisdom and strategig warfare, justice, law, victory, and the sponsor of arts, trade, and strategy. Minerva is not a patron of violence such as Mars, but only of defensive war. She was the virgin goddess of music, poetry, medicine, wisdom, commerce, weaving, and the crafts and is often with her sacred creature – an owl.

Perseus was the son of Zeus and Danaë. He also killed the gorgon Medusa with Hermes’ flying shoes and a shield made of reflecting metal.

Asclepius was the god of healing. He was the son of Apollo – also a healing god – and the mortal Coronis. When he discovered his wife was unfaithful, Apollo killed Coronis but saved the unborn child – Asclepius – who was later taught medicine by the centaur Chiron. In Homer’s epic poem Iliad, Asclepius is the father of the Greek physicians at the siege of Troy, Machaon, and Podaleirius.